Eye For Film >> Movies >> Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? (2013) Film Review

Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?

Reviewed by: Anne-Katrin Titze

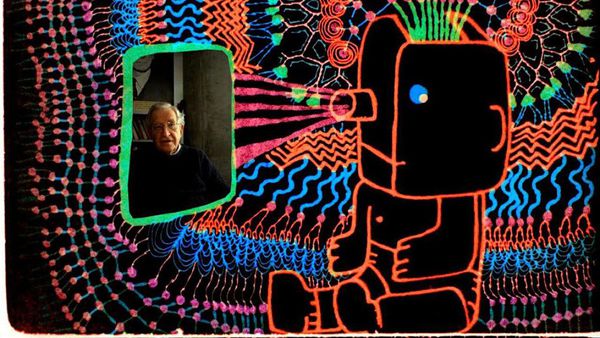

Michel Gondry ingeniously animates his conversation with Noam Chomsky, 98% through his drawings and the rest filmed with his old mechanical Bolex camera. He asks Chomsky about the first memory of his life and the answer includes a kitchen counter, oatmeal and an aunt. "Children know a lot of language before they can exhibit it," the linguist states, and says that he barely remembers high school, a dialogue accompanied by Gondry's drawing of boys riding their bikes through a forest.

You should be puzzled. Isaac Newton demonstrated that there are occult forces and inherent mysteries - the world is not a machine. Psychic continuity is a property we impose on things. "Let's be puzzled about what seems obvious," is a wondrous invitation. Teleportation instructs a bid.

The moon is an illusion. Gondry's animation mutates as we hear of evolution, Newton and Hume. How do we identify something as a tree? Gondry's unique approach to a filmic portrait of a thinker is at its best when he illustrates specific questions of the brain. Words disappear. Pens the colours of the rainbow have a go at Plato. Chomsky answers Gondry's questions, tweaks them to go where he wants to go and Gondry takes up his direction in drawing the way. "We have fixed capacities. I can't fly," says Chomsky. He talks about his life, explains evolution and mutation while Gondry draws his own visual interpretations. It is fascinating to watch as it becomes more and more obvious that we are looking at two curious and curiouser minds at work discussing the "complex continuity", the property we place on the world around us. Why we know that the transformed frog is still an enchanted prince and what needs to happen for us to no longer call a river a river - these are the questions tackled.

Chomsky comments on Asperger Syndrome, "half the people on the corridors of MIT have it," and our drive to find causes. Infants do it instinctively, we always look for the agent behind it all. Gondry exposes "life full of coincidences" into patterns and shifts the grammar of what we consider a documentary. Chomsky is pushed to talk about the death of his wife and wants to go back to happy matters.

Sometimes, the language barrier shows itself and Gondry, for example, misunderstands the English word "yield" as "eel", which leads to fetching fish drawings that illuminate communication splinters instead of hiding them.

Michel Gondry with Noam Chomsky on his shoulders dauntlessly walks a tightrope of structural proximity and structural distance.

Reviewed on: 11 Feb 2014